SKATE // 19 DEC 2025

MAKING ADAPTIVE SKATE EVENTS

There are two components to making an adaptive skate event. First, community networking and collaboration, second, the creation of skating and skate park specific adaptations.

Over the past three years, I have facilitated four large group skate events for folks with visual impairment. My interest in hosting these events was born in the empty space where information about inclusive skate programming should have, but didn’t exist.. As the concept of adaptive skating swirled in my head, I knew that in order to bring ideation into reality, I needed to make contact with a group of people willing to experiment.

After reaching out to multiple organizations with no word back, I found a group that matched the ethos of my intentions: Western PA Blind Outdoor Leisure Development (BOLD). The members of BOLD were apprehensive when first asked to team up with Switch and Signal Skatepark. So, the owner of the park Kerry Weber and I packed up some skateboards and padding and attended a BOLD board meeting. We opened up the conversation about how skateboarding could be made more approachable and the BOLD board members bought in. We held our first adaptive skate event on April 28th, 2023.

Butter Mag is a 100% reader supported publication. By subscribing to Butter’s Patreon for as little as 2$/month, you keep Butter churning, so that together we can create a more diverse outdoor sports community.

The community collaboration continued as I began to research adaptations focused on visual impairment to prepare for the event. I met with volunteers from the Library of Accessible Media for Pennsylvania where I was introduced to the concept of tactile changes on flooring to indicate the locations of items like desks and sinks. I collaborated with a library employee, named Stephen McMillen, who runs a tactile social group. His work at the time focused on translating famous art pieces into tactile images and creating tactile maps for special events and local geography. Drawing inspiration from the library, personal research, and independently reaching out to an established blind skater, Anthony Ferraro, I developed a comprehensive list of skate event adaptations.

The concepts I drew from my research consisted of two categories: structural adaptations and adjustments to teaching techniques and gear.

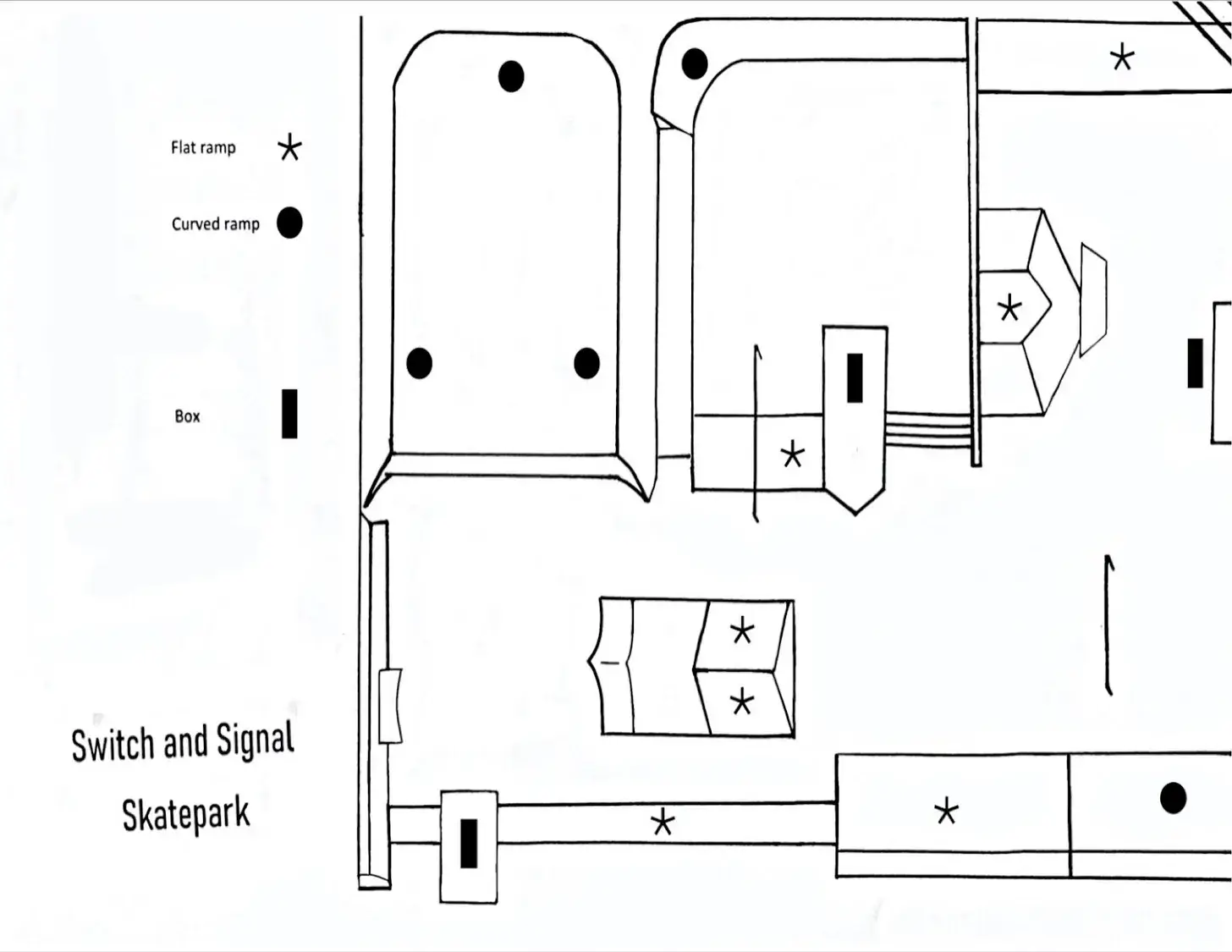

The main structural adaptations we’ve incorporated are a tactile map upon entering the skatepark and high-contrast / tactical indicators before freestanding obstacles and sudden drops. These adaptations are inclusive for participants with a large range of vision, from full blindness to tunnel vision.

Imagine walking into a building for the first time with your eyes closed. All the information you have on your surrounding area consists of what you can immediately touch and hear. Now imagine walking into that same space and finding a tactile map. This map allows you an overview of the space without having to cautiously explore the area. This becomes incredibly useful when you enter an area, like a skatepark, that has unpredictable and dangerous terrain such as free-standing rails, large drops, and obscure bowl systems. Tactile maps are an extremely useful accommodation that can easily be added to any existing park to effectively introduce new faces to the space.

There are multiple ways to create a tactile map; maps can be 2D with raised lines or small 3D replicas. Remarks from the general skate community convey an interest in 3D replicas of skateparks as they serve both as a point of accessibility and a perfect opportunity to increase the number of fingerboard parks.

Another option for accessibility is adding tactile cues into the space with a thin piece of rope held in place by high contrast tape around obstacles. Finding the right rope for this is important, it has to be thick enough to feel with a cane but not so thick as to catch your wheels while skating. The high contrast tape serves as a visual cue for those with mild vision. It is important to space the tape at least 4-6 feet from the obstacle so those who depend on the tactile input have time to feel and respond to the changing landscape. These were the adaptations we applied when altering a hockey rink for our recent adaptive rollerskating lessons. The high contrast tape guided participants, and bright tactile markers indicated the entries and exits of the monochromatic rink.

Due to the lack of universal systems to support people with visual impairments, participants require some initial explanation of these adaptations but they still enhance the comfort and independence of participants when navigating skate spaces. Introducing adaptations can be done at the start of a session, allotting skaters time to orient and walk the skate space before getting geared up. This orientation period allows participants to get a feel for a space before attempting a new skill.

Skate newcomers often struggle with intimidation as the sport has a narrative of danger, and the addition of wheels underfoot can feel unstable. So, when teaching both skateboarding and rollerskating, we must start static. Sequential teaching methods ease anxiety and allow learners time to adjust to the gear before attempting to freely navigate the skate space. At our roller skating clinic, we started on yoga mats. An unexpected benefit of this adaption was the defined space created by the yoga mat.

During our first skate event, there was no tactilely defined space for individuals to practice and gain confidence. I believe this made participants anxious about their surroundings or the possibility of knocking into another participant. Yoga mats grounded skaters when initially adjusting to skate gear, and prevented rolling when, stepping on and off a skateboard or picking up feet in roller skates.

When teaching movement, it’s important to provide tracking such as a wall or , high-contrast lines. Teaching skating can also have a hands-on component but it’s important to increase the amount you verbalize when approaching and moving around people with visual impairment.

Our gear adaptations have varied throughout events. When teaching skateboarding we added lifted bolts so that participants could position their feet. Another option, shared by Dan Mansina, a famous blind pro-skater, is adding a tactile indicator under the grip tape to aid with board orientation. When collaborating with the Western PA School for Blind Children, I adapted a roller skate by attaching snowboard boot straps to the skate, allowing a student with large AFOS (Ankle-Foot Orthoses) to fit in the skate. The collaborative event with the School for the Blind used multiple pieces of supportive gross motor equipment, such as tumble form chairs and gate trainers, to expose students to skate parks.

Each event we host has gear tailored to the participants. Some adaptations, such as structural changes, can be permanent and exist as best practice within a space to help a larger array of people with visual impairment. More personalized adaptations are group or individually dependent. The goal when hosting an adaptive skate event is to offer all accommodations freely and let participants use what they find to be most helpful.

These events have given me a basic reference point for adaptations that can be added to skate spaces and added to our community’s general knowledge of inclusive teaching techniques. This could not have happened without the willing collaboration of BOLD, PGH skates, Switch and Signal Skatepark and the WPSBC. I greatly appreciate the trust and relationships that have been built through these sessions and look forward to building a better future for visual impaired skaters.