CLIMB // 01 DEC 2022

I'M NOT AN 'INSPIRATION', I'M AN ATHLETE

“[Constantly] being told that you’re an inspiration, it drives me insane,” lamented photographer, climber, snowboarder, and below-the-knee amputee Cail Soria. “I’ll be at the gas station filling up and someone will approach me and be like, ‘oh my god you are so strong.’ I’m like, dude, my gas tank was empty, was I supposed to run out of gas? People grow up with this idea that people who are amputees, everything they do is so incredibly insane and inspirational. I think that there is inspiration [in] people who have had to overcome challenges. But, the consistent calling [amputees an] inspiration for existing is frustrating. We’re capable of doing so much more [than society thinks], we’re capable of being people.”

The outdoors has been a friend to Soria since childhood. Camping with her family and growing up on a ranch, nature was a place of tranquility. Post highschool, she spent her weekends hiking with friends, a notorious gateway activity. One day out on the trail, a friend mentioned their interest in checking out a local bouldering gym, Soria was intrigued. “I was like, this seems like an interesting, natural progression. I got hooked on it immediately. I started going by myself, I would go every day before school or work, and then it just really continued to spiral,” she laughed. “I never stopped after that.”

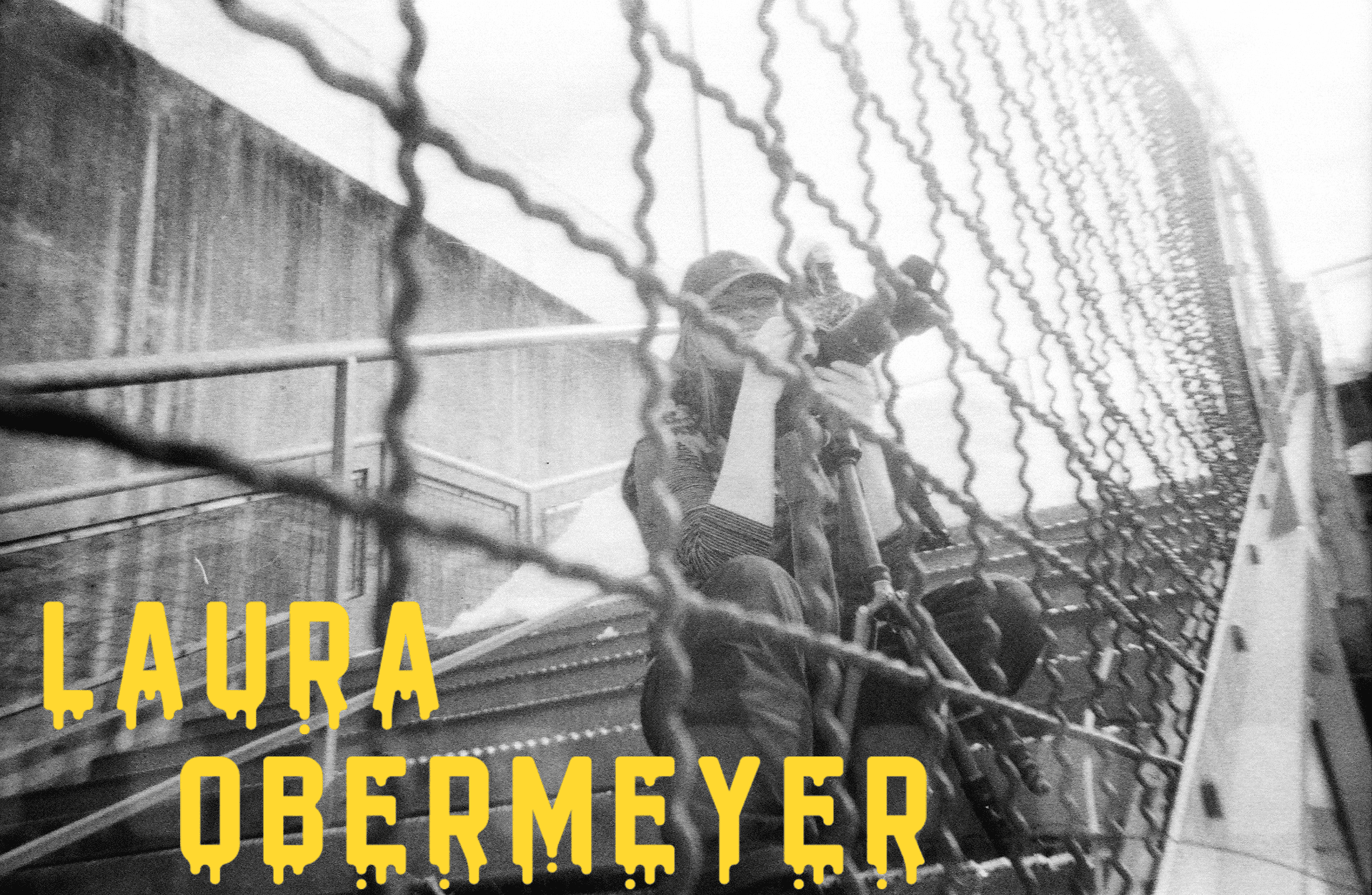

Training hard, she pushed her skill level, always looking ahead to the next grade. Growing alongside her climbing ability was Soria’s photography. Fully immersing herself in the outdoor community, Soria’s passion for capturing authentic moments as an adventure photographer ran free.

In 2017, Soria’s adventuring was put on pause when she fell over 25 feet onto solid rock while climbing. “I shattered my leg and ankle and broke my back,” she explained. “I was responsive the entire time and I was like, okay I definitely injured my leg, I could also tell that I broke it in a spot where I probably shouldn’t move my back. That was my first thought, and then my second thought was, I don’t think I’m going to be able to make it to work today. When they came down to get me I was like, do you think there’s any way I could get my climbing gear? I knew I’d hurt my back, but because my adrenaline was pumping I didn’t understand the severity of the entire situation at the time.”

Pulled back over the cliff, Soria was immediately taken to the hospital. Kept there for a week, she was eventually sent home in a wheelchair that she would use for the next three months. Fast-forward five years, in the Spring of 2022 Soria underwent her seventh and final surgery to have her below-the-knee amputation.

There was never a doubt in Soria’s mind that her leg would be removed. Given her level of activity, she knew that trying to save the limb would be futile, but due to requirements set in place by the medical system an effort to save the leg had to be made. “Insurance works in a way where you have to have a certain amount of surgeries and go through a certain amount of things before you get it amputated,” she explained. From cortisone shots, to a myriad of different braces, and even various shoe inserts, no potential solution was discounted. “It proves that you’ve already tried everything and nothing’s going to work.”

Seven surgeries, seven times on bedrest, seven times going through recovery, each time knowing that she would be thrown back into the cycle again. It’s an exhausting and brutal process, but between every surgery Soria was determined to get back outside. “We’re here, so we gotta do what we gotta do to enjoy life. It was consistent. There was no surgery where I had to fully quit doing stuff outdoors, but it definitely became more difficult and more painful,” she grinned before continuing, “It was worth it.”

“My leg works better most days [than it did before the amputation],” she said. “It does hurt a little bit because I can’t help but mourn all that lost time on bedrest even though I knew this would be the outcome.” Now, grateful to have finally removed the chronic pain and frustrations associated with her recoveries, Soria was raring to get back to the mountains to push her abilities again.

Four months post amputation a friend invited Soria out to go climbing. It was an instant yes. ““When I first climbed post amputation, I was hardly walking on my own and I ended up climbing better than I was walking, which is so funny to me.” Still, Soria couldn’t help but be a little anxious going out but not because of a fear of climbing. She would be facing the reality of climbing without her leg, and a part of her worried that routes that were once no problem would forever be out of her reach. “I knew going back out climbing for the first time as an amputee, I would be disappointed if I couldn’t climb a single route, “ she explained. “What was hard for me is to really [shift] my mindset [to], I’m going to be okay if I don’t top out this route. Even though I was telling myself that, I knew if I didn’t do it, I would be disappointed. I was more nervous about the mental aspect of being jarred with [the changes in] my physical ability at the time. I did end up topping out [though].”

Working with her physical therapist, Soria continues to build back her strength while mastering new techniques and strategies to climb with her prosthetic. “There’s a lot you have to adapt to. I can’t move my ankle anymore. I was like, oh, wow. I did use my ankle a lot while climbing,” said Soria. “Now I have to figure out different ways to compensate for that. It’s been a process for sure. At times it felt impossible. Like it would never be able to happen, but I just kept waking up in the morning [and making it happen].”

Climbing in the fall and now getting stoked for snowboard season, the only barrier that seems to stand between Soria and her drive is access to affordable adaptive equipment. Different sports have different needs and as a multi-sport athlete, Soria needs prosthetics that fit the bill. The extreme arch and small size of her climbing foot, one of the only high performance options available on the market, would send her toppling on her snowboard. Her lifestyle demands versatility, but as is the case for many adaptive athletes, Soria is blocked by finances. “As far as sports prosthetics go, it makes me sad that it’s not accessible for a lot of people, including myself,” she said. “Like having a snowboard prosthetic that I could really use because I’m a more advanced snowboarder is thousands of dollars and insurance doesn’t cover that. They won’t cover a full secondary leg for sports.” Thankfully, Soria will be going into this season fully equipt. Through the support of various organizations, she has received both a snowboard leg and secondary leg. Soria could not be more grateful for the upgrade and has already hit the slopes several times with her new hydraulic foot.

Anticipating her amputation, Soria dove into research on prosthetics and what to expect during the recovery process. She wanted to prepare herself. There was however, a blindspot in her investigation. “One thing that I didn’t know how to do research on was other athletes that are adaptive because I don’t feel like there is a lot of representation in the outdoor media,” explained Soria. “I was desperate to find someone in the community or just people in a similar situation.”

With the help of her friends, Soria slowly began to discover other adaptive athletes such as Vasu Sojitra and Maureen Beck. Digging into the community, a wave of relief washed over Soria. “It’s good to see people represented because it’s like, oh, they did this. Which means it’s possible,” she explained. “Because there was a point in time where I [thought I’d] never be able to climb the grades I was climbing before ever again. Like, that’s just off the table as an amputee. Then I found out that’s not true. I sold myself really short and having a community and people in general who are motivated and have been out here doing the same thing, [it lets people know] things like this are possible. Amputees as a whole, we’re capable of doing so much more than people would have thought and I think it’s very powerful and motivating that it’s not just one person [defying society’s expectations]. ”

It’s not just in the adaptive athlete community that she wants to see more representation. Soria has long preached the importance of highlighting BIPOC athletes and other marginalized communities in the outdoor industry. Becoming a part of one of those communities, the message hit much harder. “Being in this situation has [shown me] the importance of having representation and the ways that you can be affected without it,” reflected Soria. “I would have never known before, even though I claimed to be an ally. It’s given me a brand new perspective on how truly important diversity is in the industry.”

Before her amputation, as she probed the adaptive community, Soria shared her journey on TikTok. Connecting with athletes across the country, she was staggered by the wave of support that followed. From tips for extremely specific issues, to sending feet to try out in the mail, Soria’s gratitude to strangers on social media who’ve lent a helping can’t be overstated. “I think [just asking questions is] a really good idea”, Soria recommends for other adaptive athletes searching for answers. “[Say] this is my situation. Do you know anybody? Because somebody’s going to know somebody.”

Expanding her community beyond the boundaries of social media, Soria traveled in October to the Adaptive Climber’s Festival where she hosted a clinic on adventure photography. Looking forward to the event at the time of being interviewed, Soria shared her hopes. “I’m really stoked to see how different disabilities translate to the outdoors. People in wheelchairs that are climbing like, how does that work? I have no idea. I would like to be immersed in all the diversity of the group itself while having this common issue of accessibility.”

Representation is Soria’s mantra moving forward. As a photographer and videographer she wants to shoot projects that celebrate diversity of all forms. In the works now is a short climbing film about her local climbing gym and the importance of getting people outside. By focusing on her passion for media, Soria hopes in turn to uplift athletes of every gender, race, and body type. “The dream is to just be a part of a really fantastic film crew, either behind the camera or in front of it,” she smiled. “Either way works for me. Just having a very powerful, diverse group of people instead of hitting some quota.”

When adaptive athletes are highlighted in the media, there is a prevalent theme to their narratives. It can be summed up in a single word: despite. She can rock climb despite her amputation. He can ski despite using crutches. She can skateboard despite being in a wheelchair. You can continue to live life despite this difference that society assumes would utterly disable you.

Adaptive athletes are not overcoming themselves, they’re overcoming the sloper to crimp move on their climbing route. They’re overcoming the icy moguls as they ski down the mountain. They’re finally landing that trick they’ve been working on for months. These accomplishments are not despite anything, they come from who the athlete is and always has been.

Thus, the goal of all of Soria’s efforts is not to inspire, it is to provide an example.

“Inspiration, that’s a great word inspiration, but if everything you do is inspirational it makes it feel demeaning because your existence on this Earth [is seen as] so difficult. There are hard times, it’s definitely not an easy thing to go through and I’m still dealing a lot with it, but I think being told that for everything you do, that you’re an inspiration, it’s exhausting,” said Soria, so she rests. Camping alone or going on sushi dates with friends. Doing whatever she needs to do to unplug, Soria maintains the delicate equilibrium of her mental health and her determination to grow awareness for the adaptive athlete community. “There’s a balance between being in front of the camera and being behind it, going forward I’m looking forward to showing the journey. I think it’s a really fun one and it’s a very specific one, but it’s something where, if I can even say an offhand comment that can help somebody, I think that’s really cool. Just show that, oh yeah, this person’s normal and they’re missing a leg.”