SNOW // 01 JUNE 2022

A QUEER WAY TO SKI

“Heteronormative society’s conception of gender and sexuality is that queer is an adjective, but it’s also a verb,” explained inclusivity advocate and skier Hank Stowers. “It’s a verb because it’s the way that queer people exist and interact with the spaces that we’re in. As a queer, non-binary person, when I step into a space or in the spaces that I exist in, I don’t leave my queerness at the door. I bring that into spaces that I’m in, and I want to be able to have a relationship with my identity in all the spaces that I’m in.”

The child of ex ski instructor parents, Stowers was skiing as they were learning to walk. “It was symbiotic, which is a super cliche and classic way that middle class white kids get into skiing,” they laughed. Stowers was immersed in the community and culture of skiing throughout their childhood. Receiving scholarships to training programs and participating in ski competitions. Once out of high school, Stowers schussed to become a professional skier.

Moving to Summit County, Colorado to pursue a skiing career, Stowers felt smothered. Stuck in the closet amidst a culture teeming with toxic masculinity and glorification of substance abuse, Stowers felt they couldn’t really be themself. “I was sad all the time. I didn’t know how to be an adult,” explained Stowers. Eventually Stowers hit their limit. “I got super hurt and then I was like, fuck skiing. I’m quitting skiing. I’m going to college.”

Leaving skiing behind in Summit County, 20 year old Stowers attended Colorado State University. In this new space, Stowers had the room to reflect upon their gender and sexuality. Previously, they had accepted themselves as a man who was “hetero-flexible” and comfortable with femininity, but upon further reassessment of their identity, those labels didn’t sit quite right. In this time of uncertainty and questioning, Stowers was greeted with open arms by the queer community. “They didn’t put pressure on me to be a certain thing,” they explained. “It was the first time I was in a community where my curiosity and exploration was celebrated and met with joy and support rather than consternation or confusion.”

Upon graduating from college, Stowers sought a place where they could still be surrounded by the support of the LGBTQ+ community. So they moved to one of the most LGBTQ+ friendly cities in the States, Portland, Oregon. Only an hour drive away from Mt. Hood, Stowers began to ski casually for themselves. Separating the sport from past negativity that had surrounded it, Stowers realized that they still fostered a deep love for skiing and decided to re-approach becoming a professional skier, this time as their authentic self.

More comfortable in their identity, Stowers found that they were better able to understand and enhance their style and approach to skiing.

“I think the way that I ski has always been less aligned with a traditional masculine idea of free ride skiing, becoming aware of my gender identity and being a non-binary skier over the past two years, I had a series of revelations about why I ski, how I ski, and then doing it on purpose has made me a better skier in ways that I want to be,” explained Stowers.

“I want my skiing to look like dancing when people watch me ski. When I ski for myself I want it to feel and look like a choreographed contemporary dance down a mountain. That’s when I feel the best in my skiing and it’s definitely when I ski my best. Specifically, I like to describe my skiing as bouncy. It’s something that I value a lot in my skiing and I think that’s definitely a queer part of my athletic identity.”

Determined to take themself seriously as a skier, Stowers found themself in a difficult starting position. It was Fall 2020 and Stowers, recently fired from an already poorly paying job, was broke. Needing money for skis and perhaps slightly more importantly, rent, Stowers looked to where many of their friends in the queer community were finding fiancial stability, the sex work industry.

“I was like, me, I want to do that,” smiled Stowers. “It was intriguing to me. [It] looked like something that I could do for money but also I think that the space that you occupy in that industry as a cam person or as a stripper is very gender abundant.”

After working for several months, Stowers was able to support themselves until they found a new job and they ended up saving enough money to buy a pair of skis. However, for Stowers, finances were never the primary focus of their work. Reflecting upon their experience they explained,

“I garnered a lot of respect for people who have the endurance and the stamina to do sex work full time because it felt super draining to me on a client, capitalist level. On a personal level, as far as performance and identity, it was super inspiring and it opened me up into aspects of my gender that I hadn’t found for myself yet. I was unlocking aspects of my femininity that felt, at the time, like an epiphany of my gender for myself.”

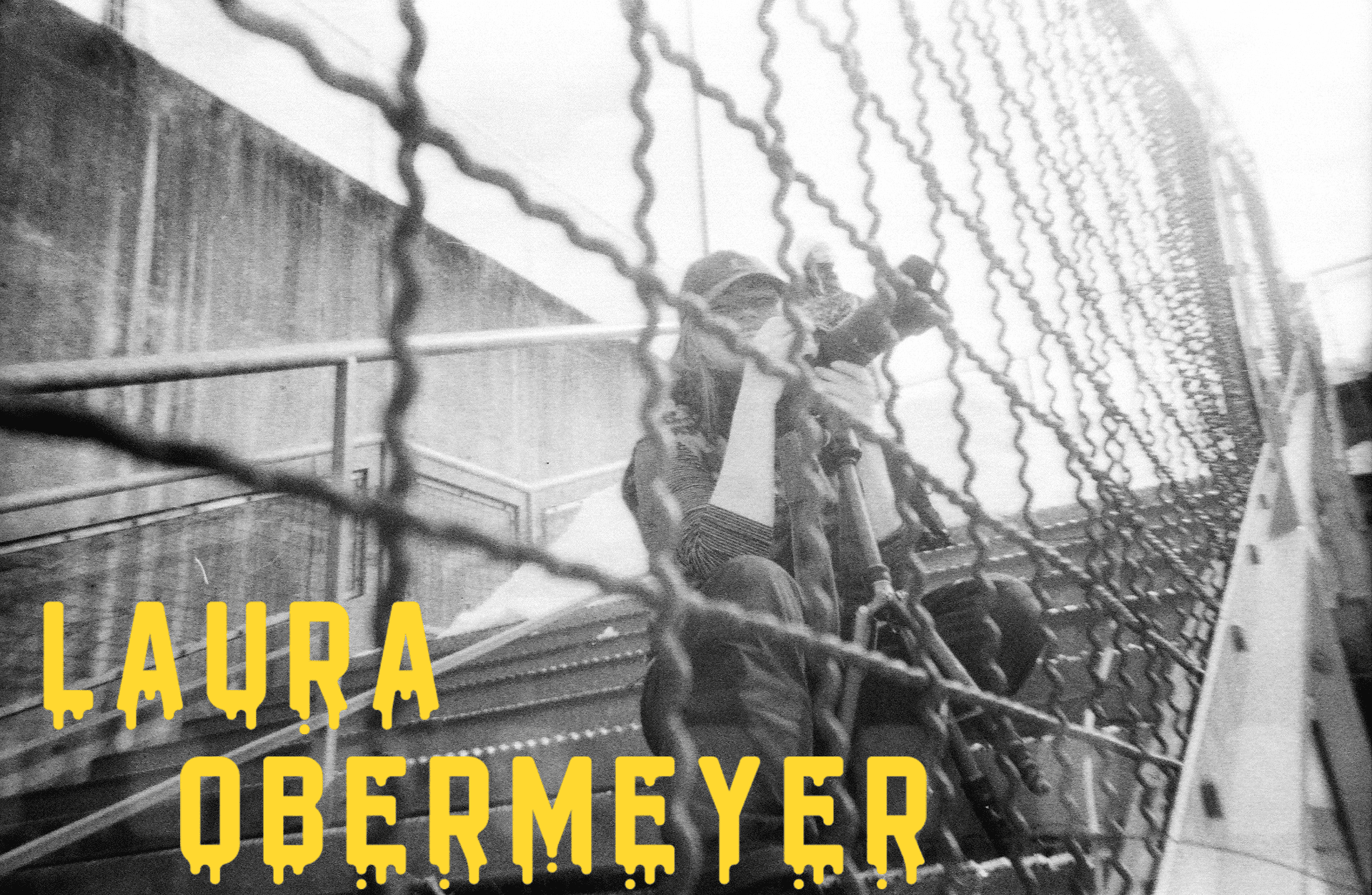

Empowered by both their return to skiing and illumination of their gender, the desire to make a ski film sprouted within Stowers. They wanted to share and celebrate their journey of gender affirmation. Validating their identity to the ski world. This desire is now better known as Maritime Air.

Split into two parts, the film takes place over multiple seasons in the Mt. Hood National Forest. Loosely retelling the narrative of Stowers’ experiences, the movie is unapologetically queer, a fact that has confused some of the film’s viewers since its release. Though the response has been overwhelmingly positive, Stowers often sees comments along the lines of “cool skiing, why’d you have to bring your sexuality into it though?” The answer to such questions is simple.

“I can’t make a ski film that’s not a queer ski film,” laughed Stowers. “I’m either going to make a bad ski film that’s a poor reflection of my identity and my story and my character, or I’m going to make a queer ski film. It has to be one or the other.”

With Mt. Hood’s extended season, Stowers and director Finn Peterson were able to ski and shoot for seven months of their year-long project. This never ending winter has made Hood a hotspot for skiers that want to prove themselves in the sport. With an expansive history of being the spot to push the boundaries of skiing, imagery of the mountain had long inspired Stowers, and was one of three reasons the team chose to focus on Hood.

The second reason the team chose to focus on Hood was to encourage the LGBTQ+ community to join them. Only an hour and a half away from Portland, Mt. Hood is a ski area in close proximity to a thriving queer community. A skier could comfortably cruise Ski Bowl in the morning and then drive back into town for a drag show with time to spare. It is in this regional space that Stowers has felt the most comfortable in their queer identity and they wanted to celebrate the diversity of the area, including Hood. As they explained, “I wanted to make a film that showed off this place, and I literally wanted the effect to be for LGBTQ people to come to Mount Hood. It is an invitation as a film. So that was a huge goal for me and probably the most important reason for why we filmed it all at Hood.”

The third reason was that snow conditions were poor in the other locations they tried to film.

An unprecedented amount of snow in March and April had Stowers and team still filming within a week of the announced launch date. In fact the last shooting day was only five days before the film came out, but for Stowers it was one of the most impactful days of the whole project. The shot is of Stowers hitting a massive road gap at Ski Bowl. The terrifying gap required a staggering 80 feet to the sweet spot of the landing.

It nagged at the edge of Stowers’ mind, but the conditions were never quite right for filming. The location has long been sought over, with multiple people reaching out to Stowers sharing their struggles and ultimate failure to jump the road. “Just a call out,” said Stowers. “If anybody knows of anybody who’s hit that gap and built it before, tell me. I’ve heard a bunch of people talk about it, but I don’t know if anybody’s ever hit it.”

What is known for certain is that Stowers absolutely sent it. After several April powder days and plenty of snow, Stowers pulled together a team to build the jump and within 24 hours they had the shot.

Due to resources and pre-existing relationships within the ski community, a majority of the people Stowers worked with were cis straight men. While deeply appreciative of the work everyone put into the project, that last road gap scene stands out to Stowers because it was one of the few shoot days where another non-binary skier was present. Having helped build the feature they were one of the only other skiers to hit that jump that day.

“So at the end of the session, it was like this queer trans jump session on the scariest jump I’ve ever hit. It was just me and one other person who’s also a non-binary/trans/fem human. That felt so cool. It felt so special that the last day was the most picturesque and meaningful scene.”

Stowers further explained that another reason that day was so meaningful to them was “because we finished the jump in the scene and I got the trick that I wanted to on the jump and it was like, oh, this is going to be a good movie. It was the first time that I stopped worrying about whether or not it was going to suck and knew in my heart [that] this is going to be good.”

Response to the film has been overwhelmingly positive and Stowers is surprised by the number of big name media hopping on board to support and promote the project. “People better watch this because I’ve worked my ass off on it,” they laughed. Though pleasantly surprised, Stowers is not shocked that the film has gotten attention, as they explained, “The hegemony and the majority of skiing is extremely heteronormative, it’s extremely patriarchal, and it’s extremely white. The lack of diversity in skiing means that films like this are controversial, which means that they’re going to get more attention because that’s how the algorithm works.”

“I feel almost kind of silly in a way about the response it’s gotten, because in my head, it’s not queer enough. There’s only a cumulative 10 seconds of me pole dancing and being a queer person. The whole film is queer, but if anything, I would have wanted to make more of it about being queer in snow sport spaces and more of me being hot and fem and yassified in the film.”

Using whatever notoriety they’ve gained through Maritime Air, Stowers hopes to amplify more queer voices in future projects. “One of the biggest things that’s happened as a result of this film, both creating it and releasing it, is a flood of awareness of how prevalent queerness is in the ski community and how it’s not talked about. But there is a huge LGBTQ+ community in skiing.”

Stowers smiled.

“Ultimately my super genius goal is to make skiing not such a shitty place for people who are not part of [the dominant] culture. Because that’s what makes skiing the most fun for me, having a variety of people from all walks of life that can bond over this silly snow sliding thing that we love to do. It sounds generic, but if more people could do that and if more people from different stories can do that, I think it would become a cooler place to be, and it’d be more fun and it’d be more interesting.”

Through projects such as Maritime Air and Open Slopes PDX, a group that fundraises and provides resources for BIPOC folks interested in snow sports, Stowers works to make this dream a reality. By highlighting LGBTQ+ ski culture on Mt. Hood, they hope to transform the mountain into a queer space, eventually normalizing diversity across ski slopes everywhere, or as Stowers said,

“My devious end goal is to yassify Mount Hood,” they grinned. “I want it to be a capital for snow sports, but I think that it also has this huge potential of being the place that queer skiers meet up and recreate and link. The temperature is warm, we can wear hot crop tops, we can wear gay shit. We can dress in our best selves.”

“I do want to thank the queer community who have made themselves known to me and who are in their space, being who they are. Whether you’re out or you’re not, it’s super meaningful and valuable and motivating to know that there are other people who are queer in this space.”

For any queer skiers or snowboarder who find themselves on Mt. Hood without a friend, Stowers insists, “Connect with me. Let me know. Hit me up.”