CLIMB // 01 JUNE 2023

FROM CITY LIGHTS TO MOUNTAIN HEIGHTS

“There’s so many different identities that you grow up under. They inspire so many different kinds of behaviors in you. I think one thing about being specifically gay or having an alternative sexuality, is that it’s an identity that is pretty easy to hide,” explained non-binary climber Thomas Bukowski, who as a Hong Kong American is very familiar with the balancing act of intersectionality. “You learn to hide it as a way of survival. It’s a way of making your life easier, less overwhelming and less intense when that’s what you need. So I was surprised at how scary it felt, the idea that I should be more visible as a gay climber in 2021. Even though I’ve lived in San Francisco for a decade. I thought I was done [coming out]. I was really surprised.”

Bukowski did not dream of being a climber when they were a child. In fact the outdoors were the last thing on the young Hong Konger’s mind. “I was a computer nerd growing up,” they laughed. “I was skinny and wasn’t really athletic at all. Hong Kong doesn’t have the same kind of tradition, at least in the US, of having a lot of athleticism and sports in school for kids. [Plus] it’s a very dense city. It’s a lot like growing up in Manhattan, there’s not a ton of green space.”

Aside from the occasional bike ride and eventual enlistment onto a swim team, Bukowski spent most of their time, as many millennial children did, exploring the brand new world of the internet.

However that all changed when Bukowski moved to Norway for his last two years of high school. It was there that he met 1980’s British climbing icon Chris Hamper, who just so happened to be his physics teacher. “He ended up scrubbing and cleaning a couple of crags right by the school, as you do when you move somewhere as a climber,” explained Bukowski. “That was how I started. He was the one who taught me how to climb. It’s kind of a funny way to start. [Of course] I got super hooked and I went all the time.”

Living in rural Norway, Bukowski’s climbing community was made up entirely of other students who’d been bitten by the climbing bug. So his introduction to sport climbing by Hamper, and trad climbing by another teacher at the school, Alistar, did not carry the competitive attitude that’s found in some communities. “Norway was very blissful,” smiled Bukowski. “You would just ask around to see if anyone wanted to climb. If they wanted to climb, you’d go grab a rope, some draws and shoes, and you’d just go and climb.”

He smiled, “My entire two years in Norway were really a magical experience in a magical country.”

Post graduation, Bukowski moved once again, relocating to Hanover, New Hampshire to attend Dartmouth College. Along with integrating himself into American culture, Bukowski also found himself confronted for the first time with the challenge of breaking into a long established climbing community. “They had an outing club that organized climbing trips and things like that,” he explained. “It was much more like, oh, there’s a climbing trip, but you have to apply for it. And I didn’t get in because they didn’t feel like I had enough experience.”

Though the local climbing scene was intimidating, Bukowski quickly found themself swept under the wing of the school’s resident dirtbag professor. “My most salient memory about climbing out there is this guy John Joline,” they recalled. “He was in his early fifties at that point. He had lots of wisps of white hair, talked really fast, an animated kind of guy who was just perpetually psyched to go rock climbing. I would teach intro climbing classes with him. Help people into their harnesses, run up a couple of 5.7/5.8 routes to put up some ropes to top rope, things like that.”

They continued, “But I remember once we were climbing in Rumney, [just the two of us], and I was trying a 10d or 11a or something like that. He said this thing to me out of the blue. He said, ‘You know Thomas, if you give this thing a little bit of time and effort, you could be a pretty good rock climber.’”

While it may have been an off-hand comment for Joline, for the 19-year-old Bukowski, who’d just moved to the United States without knowing a single soul, it meant a lot.

As they explained, “I think in a way, it gave me permission to think that maybe it’s okay to spend more time and get more interested in this weird sport that I seemed to be doing.”

However, the self-assurance to fully commit to that idea was still some years down the line as Bukowski still found himself intimidated everytime he walked into the climbing gym. “I think climbers, they’re folks that tend to have a decent amount of self confidence,” he said. “Climbing as an activity gives you a lot of confidence because you’re like, I’m going to try this hard thing, and then you do it and you’re like, oh, I can do hard things. That’s one of the great things about climbing. But [at the time] I found it all pretty intimidating.”

Two years into his undergrad, Bukowski realized that Hanover was not where they needed or wanted to be. He wanted to be somewhere where he could explore his queerness openly, so he moved to San Francisco. But even with finding queer community as his primary motivator for moving across the country, it had to be put on the backburner for a bit. As he explained:

“When I dropped out of college and was like, whoa, now I’m really just a small fish in a really large pond. Because in some ways I was an immigrant. I didn’t have any family here. I didn’t really know anything about this country. But then I was like, okay, I should get a job, figure out where I want to move, and just figure out how to live in America. A lot of the time there were much more pressing just things to deal with than exploring my sexuality and my identity more. I had to find a job, find a place to live, figure out how to make pasta. [Because at the time] that was much more pressing. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, you know?”

Thankfully Bukowski did eventually figure out how to cook that pasta and was able to immerse themself in the queer culture of San Francisco. They’d done it, they’d reached the gay mecha. The journey was over, or so it seemed. But, as Bukowski explained, it was not quite that simple.

“For a while I thought, I moved to San Francisco. I’ve lived here for a couple of years. I’m done. I’ve finished my struggle as a gay person,” they said. “But then I realized, after I learned a little bit more, homophobia is also internalized, right? The things that were holding me back in terms of fully expressing myself, living a more full version of myself, and holding me back from happiness around my sexuality, were actually inside me.”

This was most apparent in how Bukowski compartmentalized their life. Work, climbing, and queerness each had their own lane in their life, no crossover. As Bukowski explained, “There was work, and it was a part of my life where I’d have my work friends and talk about work things. Then there was part of my life for climbing, when I’d go on trips on the weekends. And there’s part of my life that was my gay life. That’s when I’d go to the Castro and maybe not go climbing that weekend. I had these compartments, which can totally be healthy, and I just didn’t really commingle those things.”

Still as the years passed, Bukowski began to look for queerness in the other parts of his life. A decade of climbing in Yosemite Valley with no queer friends was starting to feel a bit lonely. “I just never met another person that was gay. And for a little while it’s kind of like, well, whatever, it doesn’t really matter. I just want to go climbing,” he explained. “But then after five years, then you [begin to ask], are there other gay people in climbing? You look to those places where you spend a lot of time naturally for understanding, belonging and a sense of place. I was doing that too and I was just like, how come there are no other gay people or queer people here? What’s up with that?”

He continued, “For many years, as I got more into climbing, I would ask my friends who were more in the scene in Yosemite to let me know if they ever ran into another gay climber. At that point, I was looking for a friend, someone else who has a shared lived experience.”

As Bukowski dug deeper in the climbing community for queer camaraderie, he found some respite at the queer meetups hosted in local climbing gyms. Yet, it didn’t quite fill the need. “I thought about that a lot,” he said. “What about someone who goes to the gym once or twice a month who lives in San Francisco. There’s plenty of queer and gay people who do that. Why not go hang out with those people?”

But by that point, climbing consumed a large portion of Bukowski’s life. It had solidified itself as a key part of their identity. What they were really looking for were friends who could meet them at the same level of passion for the sport while sharing that experience of being queer.

It was at this point that Bukowski decided to make their queerness more visible. He wanted other gay climbers to be able to recognize that they weren’t alone. This was however, much easier said than done. But Bukowski was determined to merge the previously two segregated channels of their life, climbing and queerness, no matter how long it took.

Luckily Bukowski’s motivation was boosted by an AMGA Single Pitch Instructor course specifically for those within the queer community. “I wasn’t sure I even wanted to be a guide. I just wanted to hang out with other queer climbers that were [committed to the sport],” they explained. “[Then] Nikki Smith came and gave us a speech like, ‘Hey, you people in this course who check various boxes and are part of various affinity groups and have these intersectional identities. You have a lot of power in the outdoor industry and there’s a lot you can do about representation and diversity in this world.’”

“[It was like], you can do something, right? And also a little bit like, you better do something,” laughed Bukowski. “That was a very inspiring talking-to that I’d just never thought about before. I never thought that I could be the difference. That conversation with Nikki really lit the spark.”

By August later that year Bukowski had completed his SPI exam. Then the following weekend, he taught his first queer focused course for a group of college kids. It was the first of many as Bukowski has taught more and more clinics over the past two climbing seasons. He explained, “These last couple of years, there’s been so many more affinity spaces. It made a lot of sense to be like, cool, I’ll teach courses in affinity spaces. In a very sort of simple way, I just really didn’t want another climber who is just starting out and is queer or gay [to think], I’m the only one. I want to make sure that I can offer these courses that folks can take where you can have a queer climbing instructor. [Someone who’s] been climbing for a while, and someone to show them they can do all the hard stuff too.”

Reflecting back on last year’s clinics Bukowski smiled, “What I cherish the most about these queer climbing spaces is how much they feel just like queer spaces. I think they often are healing spaces. People were a little bit messy in the way that they arrived at this thing and that often can feel very precious. I just didn’t think that aspect of queerness would be so prominent.”

That inherent queerness does more than provide a sense of community, it allows those being introduced to new skills to feel safe in their learning. “Everyone read the email, so to speak,” said Bukowski. “That’s actually enough. [Being able to assume] everyone’s nice, respectful, and so on, that’s enough to create space. You just can’t really learn anything without it being a safe and comfortable space. It never really works. [Climbing] is an activity that requires a lot of trust and it’s quite intimate in its own way.”

Along with the joy they’ve found teaching in affinity spaces, Bukowski has begun to dip their toes into the world of professional climbing with the support of the North Face Athlete Development Program. “They put [the program] together as a way to change the face of what athlete teams and athletes in adventure sports can look like,” they explained. “It’s really neat how diverse it is. How many different kinds of people and different ways of engaging with sport there are in the program. The idea is that, hey, we’ll give these folks a contract, mentorship, support and see in two years, what can these folks do with that? How can we help these folks develop as athletes?”

“I’ve been pretty much only climbing and nothing else for the last five years of my life, but I never really thought of myself as a professional climber and what that could look like. It’s given me a different perspective on what climbing can be for me and how I can engage with it,” he grinned. “It’s definitely given me a little more fire in my belly. I’m super grateful to get to be part of it.”

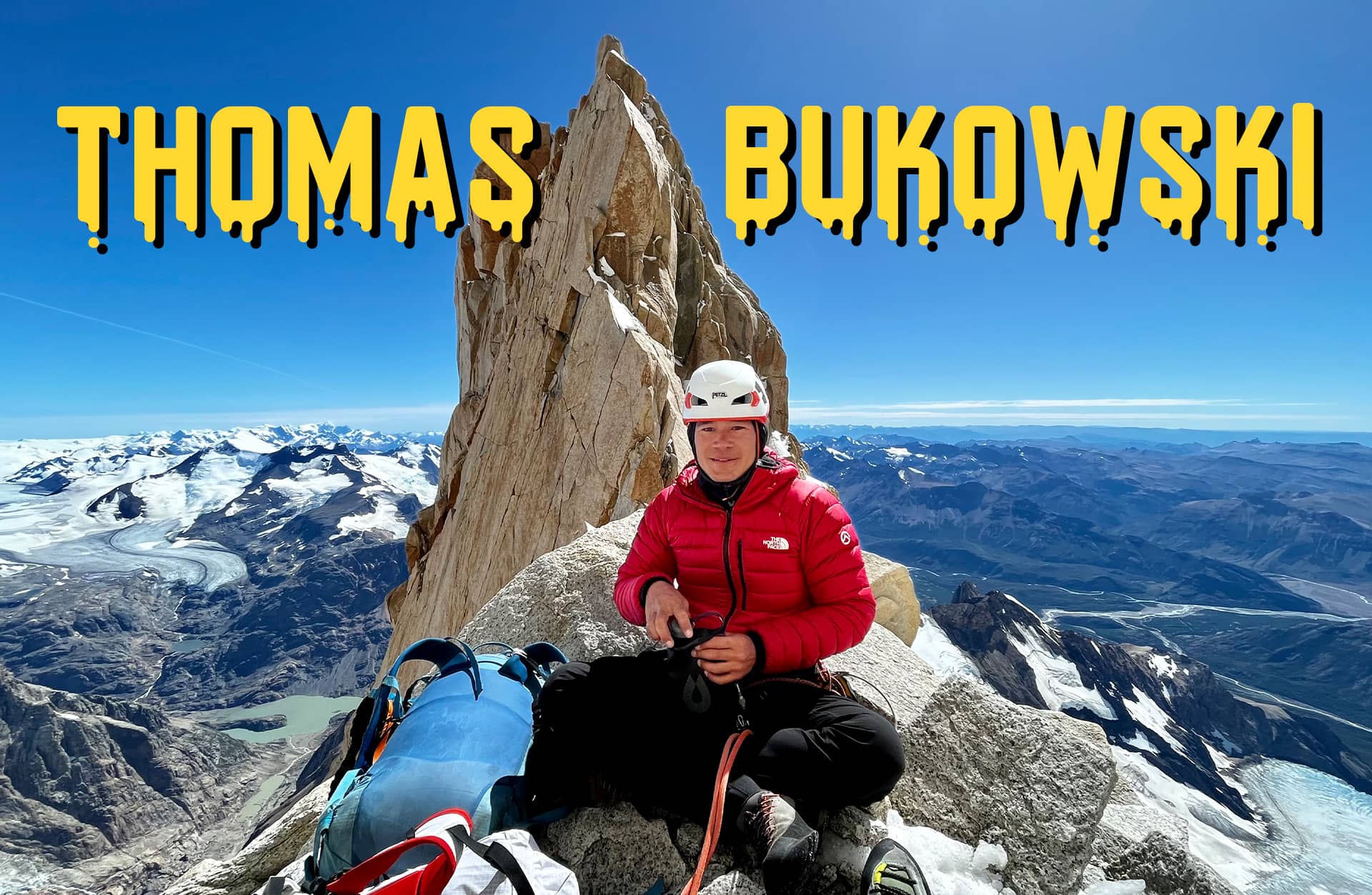

Taking advantage of that support, Bukowski is going into the next few climbing seasons with a laundry list of routes. In particular they’re stoked to return to Patagonia. “It’s just a place that feels really perfect. It matches my climbing personality really well,” they smiled. “Like, you sit around for a while and then there’s a weather window and then you go and run around with your head cut off for two and a half days. Then you come back down, you’re like, oh, God, what happened? It’s very complex terrain. There’s ice and snow. I think the dynamicness of the area is what I really find engaging.”

They continued, “The other big focus is that I’m wading into putting up first ascents and putting up new routes. That’s something I’ve always found pretty intimidating. I hadn’t really caught the spark much before, but now I’m getting more excited about it. So pretty psyched about that.”

Back on the state side of things, Bukowski has been working with friend Robin Hirsch to complete a guidebook for Tuolumne Meadows. “It’s the high country in Yosemite National Park,” they said. “It’s only open in the summer and it has a magical eternal summer camp vibe because you have long days and it’s really open up there.”

Hirsch has been accumulating an encyclopedic knowledge of the area since 2012, and Bukowski joined the project in 2019 to help get all that info organized. Bukowski was more than happy to geek out over optimizing readability of the data set of over 1,650 routes. The duo has been hard at work to get the first round of books printed by summer 2023. “Yeah, we’re still cranking away on it. It should come out this summer. But also it’s been a huge snow year, so who knows when the road will even open?” he laughed. “It’s weird to have one’s book deadline be dependent on how quickly snow melts. That is a new one for me, for sure.”

Of course, creating affinity spaces and creating more representation will always be a top priority for Bukowski. Though it may have grown in popularity over the past few years, climbing is still a niche sport. And while the intersection of those who identify with being a dirtbag climber and queer may not be the largest group in the world, Bukowski wants to create a safe space for the others out there and give the community room to grow. As they explained:

“Very few people are going to be like, ‘I’m going to really fight for my sense of belonging to go climbing.’ Because most of us have other, more important fights in our lives. I think it’s important to remember that for most sports, we’re doing them for fun. Right? This is recreation. So it’s different from workplace discrimination [which affects] one’s ability to make a living. You’re pretty incentivized, so you fight for it. But [climbing] is something where there’s a lot of amazing things that it can bring into your life, but it’s a surplus, right? It’s a cherry on the top. So, if the vibes are not good, that pretty much kills it because it’s [no longer] fun.”

But Bukowski, who holds climbing in a special place in their heart, is more than ready to fight that fight for those who can’t. “I really do think climbing is really amazing,” they smiled. “I think it’s really special. I might be a little bit biased, obviously, but I think it’s a really special thing that we get to do and that we can do. I really want other people to experience that. Because it’s done so much [for me], it’s completely changed my life.”